DEC

Stories in stone: LCCC works to preserve historic grave markers

In the Concept Forge at Laramie County Community College, Chris Allen methodically moves a wireless scanner over the surface of two objects.

“Different surfaces can be challenging, so you have to find the right approach,” Chris said.

Those objects are two grave markers, weathered by time and the elements, memorializing individuals who died on the Oregon Trail, one of the most significant migration routes in American history. Each marker tells a story, from the faintly etched inscriptions to the unique wear patterns on the stone.

The scanner, an Artec Leo, projects light to capture precise measurements and details, recording not just the shape but the color and texture of the stone. This careful process ensures that every detail of the original marker is preserved.

That’s important because LCCC is part of a unique project to preserve and replicate the markers. Once the Concept Forge’s experts have finished their work, the replicas are to be placed at the gravesides while the original headstones are preserved in a museum, ensuring their protection from damage, weathering and other potential hazards.

Housed in the college’s Advanced Manufacturing & Material Center, the Concept Forge is an innovative makerspace designed to facilitate creativity and learning in manufacturing in southeast Wyoming. It offers access to advanced tools and technologies, including 3D printers and laser systems, for both students and the wider community. This space supports a variety of projects, from personal hobbies to entrepreneurial ventures, encouraging experimentation and the development of practical skills in a supportive environment.

It’s common, for example, for a car restoration expert to come and need a part that cannot be found, which the Concept Forge can craft. Many creative projects come through the doors as well, whether it’s creating personalized key chains or wood-cut art pieces.

This project, however, was unique, said Dave Curry, AMMC director.

“I keep joking that we never know what the next call will have in store for us,” Dave said.

Stories carved in stone

The Oregon-California Trail was a critical migration route for thousands in the western

United States during the 19th century. Spanning more than 2,000 miles from Missouri

to Oregon and California, the trail guided over 400,000 settlers, miners and adventurers

through rugged terrain between the 1830s and late 1860s.

While the vast majority survived the journey, many faced relentless challenges, including disease, accidents and harsh weather. Some people died along the trail. The federal government estimates the death rate to range from 6-10%, while others, such as historian John D. Unruh, estimate the number to be closer to 4%.

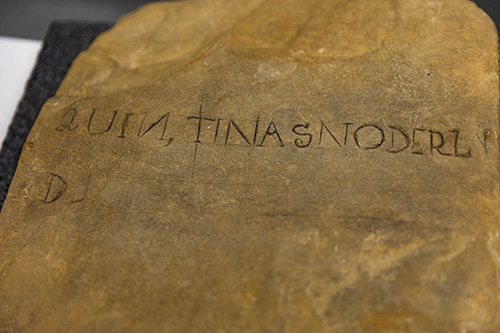

The two grave markers currently being replicated at Laramie County Community College were discovered in Wyoming, a state through which significant portions of the Oregon Trail passed. One marker belonged to Millie Irwin, who died in 1852 near the North Platte River. Her gravestone, inscribed with her name and the date of her passing, was unearthed decades ago by a rancher plowing his hayfield near Glendo. The other, belonging to a member of the Snodderly family, was found when ranchers grading an entrance road struck it with heavy machinery.

The human remains were excavated, and the gravestones were placed in a museum for historical safeguarding.

Millie Irwin, a native of North Carolina, was traveling with her husband, Robert, and their family, aiming to start a new life in Oregon. Robert Irwin and the surviving members of his family settled near Philomath, Benton County, Oregon. The Snodderlys were farmers also heading to Oregon.

This information is available because of historian Randy Brown. Randy noted that many who died on the trail were little more than names on a headstone, with no context about the lives they represented.

“It’s important to me because I can do original research and write articles, mark the trail and restore and maintain gravesides and research them,” Randy says in an email. “This was needed since many of the known graves were just names on a headstone. Nothing was known about the people.”

Going beyond practical necessity

Thinking about the lives the markers represent, Chris said he grasps the importance of the work. He Imagines a traveler sitting at a campsite, having to find a stone and carve his or her loved ones’ names in it before again having to hit the trail.

“When I think about this, it takes me back to the idea that someone cared enough to

chisel out every letter by hand,” Chris said. “At the very least, I want to honor

that effort by ensuring we capture what they created and preserve their work with

the respect it deserves.”

“When I think about this, it takes me back to the idea that someone cared enough to

chisel out every letter by hand,” Chris said. “At the very least, I want to honor

that effort by ensuring we capture what they created and preserve their work with

the respect it deserves.”

Once the scanning is complete, models will be transferred to design software, such as Blender or Fusion 360, for cleanup and refinement to make them watertight for printing. Since the stones are large, they will be printed in durable materials like PETG or ASA to withstand the elements, with larger pieces assembled using braces. The final printed models will be painted with UV-resistant paints, likely airbrushed, to ensure they closely resemble the original stones, making them nearly indistinguishable from a short distance.

Chris said there may be hurdles, particularly with the size and fine-tuning of the lettering. Adjustments might include applying powder or similar material to enhance the visibility of the letters. The process, he said, is not entirely straightforward, but he’s excited about the resources at his disposal for the project.

“First off, I’m glad to have the equipment and tools to take on the challenge,” Chris said. “I like testing my skills.”

For Dave, the project is another indication, however unimagined until it happened, of how the Concept Forge and AMMC can make southeast Wyoming a stronger community.

“If we look at our original mission — community, students, industry — it’s all about supporting the state and showcasing its history, as well as the history of the United States,” Dave said. “A little place in Cheyenne can play a big role in that, and that’s why we do it.”

It’s always a pleasure to work on projects that provide more immediate value to society, whether that’s helping mechanics, engineers, manufacturers, tourists, decorators and more, Chris said. But when it comes to making sure historical artifacts are preserved for future generations, he said he’s inspired to do the best work he can.

“I think with the conceptual side of the AMMC, we have the ability to produce car parts and other widgets, but we also have the capacity to approach these objects from a different perspective — the side of intangible societal value,” Chris said.

Go to lccc.wy.edu/manufacturing to learn more.