It’s easy to assume that a community college won’t have the same opportunities found at large four-year universities. At LCCC however, two faculty members are working hard to prove how wrong that misconception is.

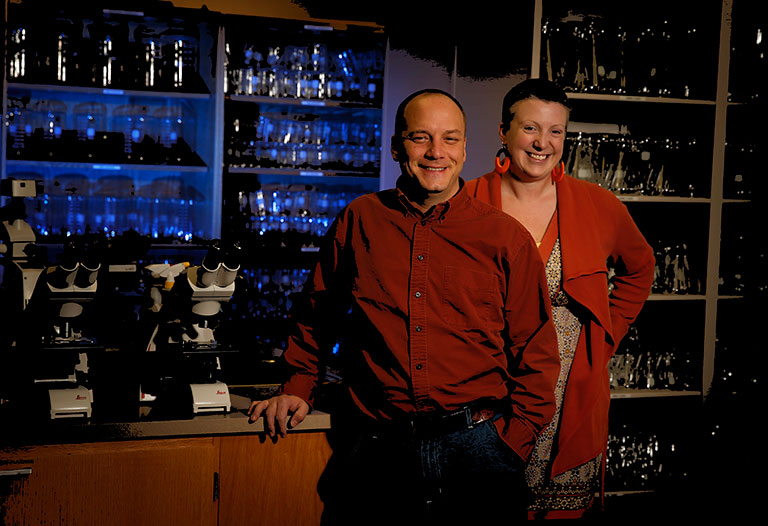

Ami Wangeline and Zac Roehrs, instructors in the biology program at LCCC, collaborated on a grant with a team from the University of Northern Colorado, to provide that school with a new electron microscope to replace the one they had. Their current model was still fully operational, but UNC wanted to try for a larger option. The grant was approved through the National Science Foundation.

“The previous microscope was no longer being used, so we asked about the possibility of donating it to us,” Wangeline shared. “They agreed, and we happily brought it up here.”

Not only does a gesture like that build goodwill between the two institutions, it also helps bridge scientific opportunities for faculty, students and research.

As both instructors acknowledge, this type of equipment is exceedingly rare for a community college to possess. Though several big universities have that equipment, that doesn’t necessarily translate to students having access to the microscope.

“In those situations, you would prepare the sample and give it to a technician to run,” Roehrs said. “We can actually teach students how to use this. Doctoral candidates don’t even get to really work on it this way.”

That kind of access not only helps draw students to the program, but it also gives them a leg up when they transfer to schools to finish their bachelor’s degrees. For example, students in Biology of Plants and Fungi were some of the first to fully immerse into an SEM project as a class, collecting samples and taking images. It went so well that the hope is to expand this opportunity to additional students through courses going forward.

To many people, science can be slightly intimidating. Without instructors or context to help give meaning to the lesson, there often is little value to the learner. Wangeline and Roehrs are both aware of that and give tremendous energy to what they teach.

For instance, most people have probably used dissecting or compound microscopes, which use light to help magnify the images, up to 1,500X in a best-case scenario. This certainly can help with instruction, but also has limitations as to the depths of discovery.

A scanning electron microscope (SEM), however, uses a beam of electrons in a vacuum that bounce off the object with magnification of up to 200,000X, giving such intricate details as the surface of a cell or extraordinarily tiny organisms living on other tiny organisms.

Preparing the specimens for viewing is an extensive and time-consuming process. Additionally, because there is no light, the images can’t be conveyed in color. However, it is common practice to add distinctive coloring to the image after the fact.

The microscope itself is an unassuming piece of equipment, found in a relatively non-descript imaging room in the Science Building. What it does though, is simply amazing to see.

“We undersell the experience of using something like this,” Roehrs said.

In fact, the SEM is being used by more than just LCCC students. In building a collaborative research environment, both Wangeline and Roehrs welcome the idea of bridging opportunities with other schools. Just as LCCC is welcome to use equipment at UNC, a student from Colorado State University was able to use LCCC’s microscopy and in particular the personnel who supported it.

“Regional schools have open doors to share resources, and we reciprocate,” Wangeline noted.

Roehrs added, “If you work in science, it’s all about collaboration.”

It’s that kind of regional collaboration that has helped a trio of students take research to exciting places.

Three former LCCC students who went on to UW were able to use the SEM, which also functions as an X-ray scanner, to determine the composition of crystals produced by fungus in the area. That research is being prepared for publication in “Fungal Biology,” a peer-reviewed science journal.

These three students are making tremendous strides as they advance in their fields: two are completing graduate school in Idaho and Texas, the third has finished an advanced degree in molecular biology and will soon be going to medical school.

Wangeline and Roehrs find the collaborative environment beneficial to schools and to students, in addition to giving credibility to LCCC.

“It works both ways. We can direct students to those schools. There are so many fields in biology. We want to help guide students into the parts that they’re interested in. The more people we can connect with, the better we can help them find schools that would be the best fit,” Roehrs said.

Like much of the rest of the college, these instructors work hard to ensure that going to LCCC is not perceived as a lesser opportunity. They also know that several students come from relatively rural areas where high schools may have had limited access to high-tech equipment.

“We want to break down that barrier immediately,” Wangeline said. “One of the great things is that we can get the students hands-on scientific skills early on. It gives them confidence and keeps them engaged.”

Molly Loetscher, a general science major at LCCC with an emphasis in biology, is thrilled to have experience with the SEM.

“The opportunity is phenomenal. It opens up a whole other world. Something so small, that you see every day, looks completely different under this microscope,” she said.

As a research student, she has done extensive field work while at LCCC and even presented papers based on her findings. Loetscher plans to continue her education after she graduates in May. Already, she knows she has an advantage compared to other students.

“When applying for lab positions, they get a lot of applications. When they see you have experience with SEM, it puts you at the top of the list and opens up a lot of positions.”

Ultimately, the benefit of obtaining equipment like this and incorporating it into curriculum is to give more opportunities to LCCC students.

“Our central goal with any of this research is student-centered,” Roehrs said. “If they go into science, it’s important for them to have experience. Even if they walk away learning that they don’t want a career in science, then I’m excited they figured that out about themselves. That’s important.”

LARAMIE COUNTYCOMMUNITY COLLEGE

LARAMIE COUNTYCOMMUNITY COLLEGE